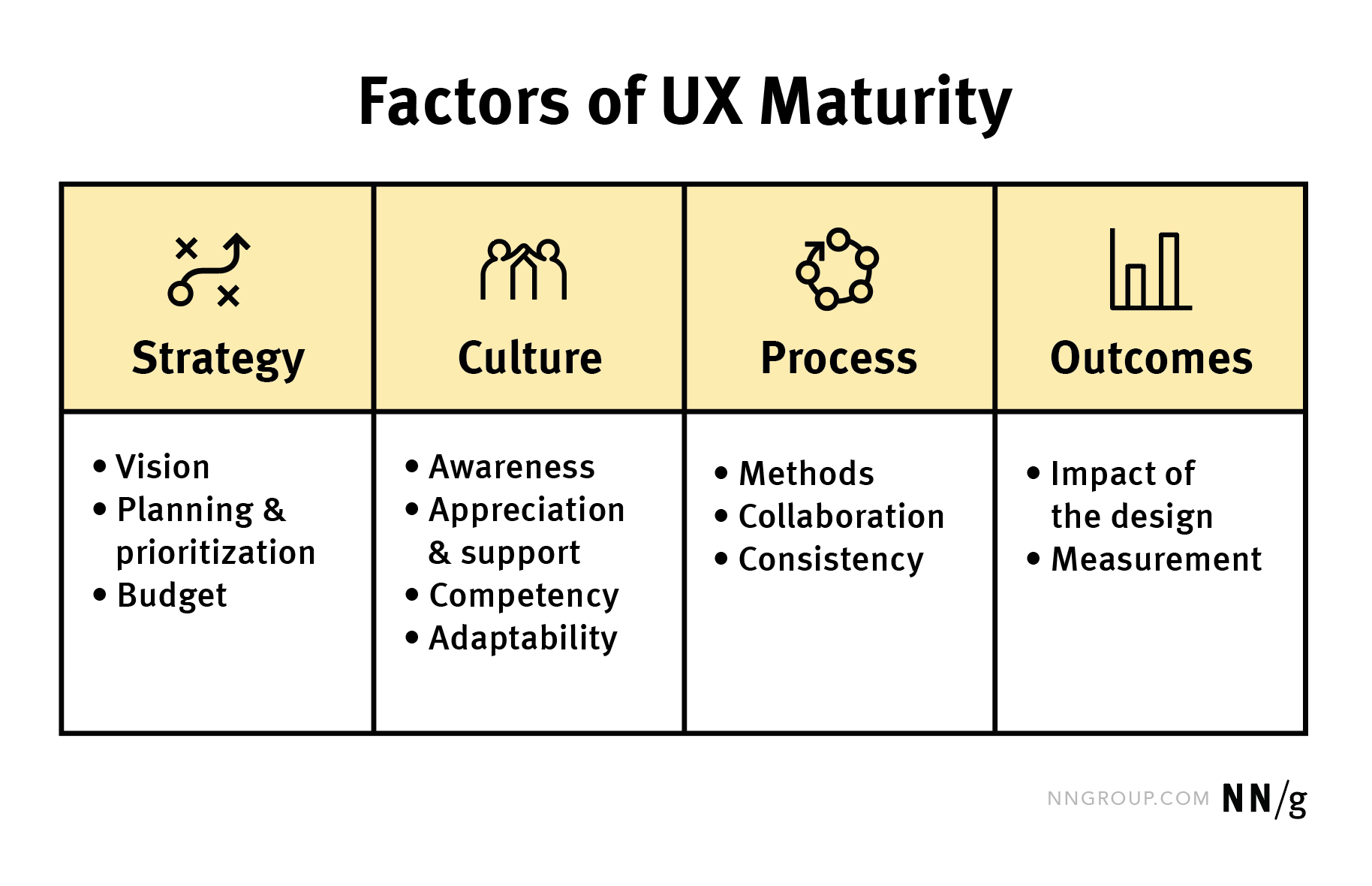

Factors in UX Maturity

Improving UX maturity requires growth & evolution across 4 high-level factors: strategy, culture, process, & outcomes.

One tool is to estimate the UX maturity: high (set up for systematic success) or low maturity (mostly fail, & ship bad design, unless you're lucky). Our UX-maturity model has 6 stages that cover processes, design, research, leadership support, & longevity of UX.

Definition

UX maturity measures an organization’s desire & ability to successfully deliver user-centered design. It encompasses the quality & consistency of research & design processes, resources, tools, & operations, as well as the organization’s propensity to support & strengthen UX now & in the future, through its leadership, workforce, & culture.

The UX-Maturity Model

The UX-maturity model provides a framework to assess each organization’s UX-related strengths & weaknesses. We can use that assessment to determine which of the 6 stages an organization currently occupies. Further, this model provides insights about how an organization can increase its UX maturity.

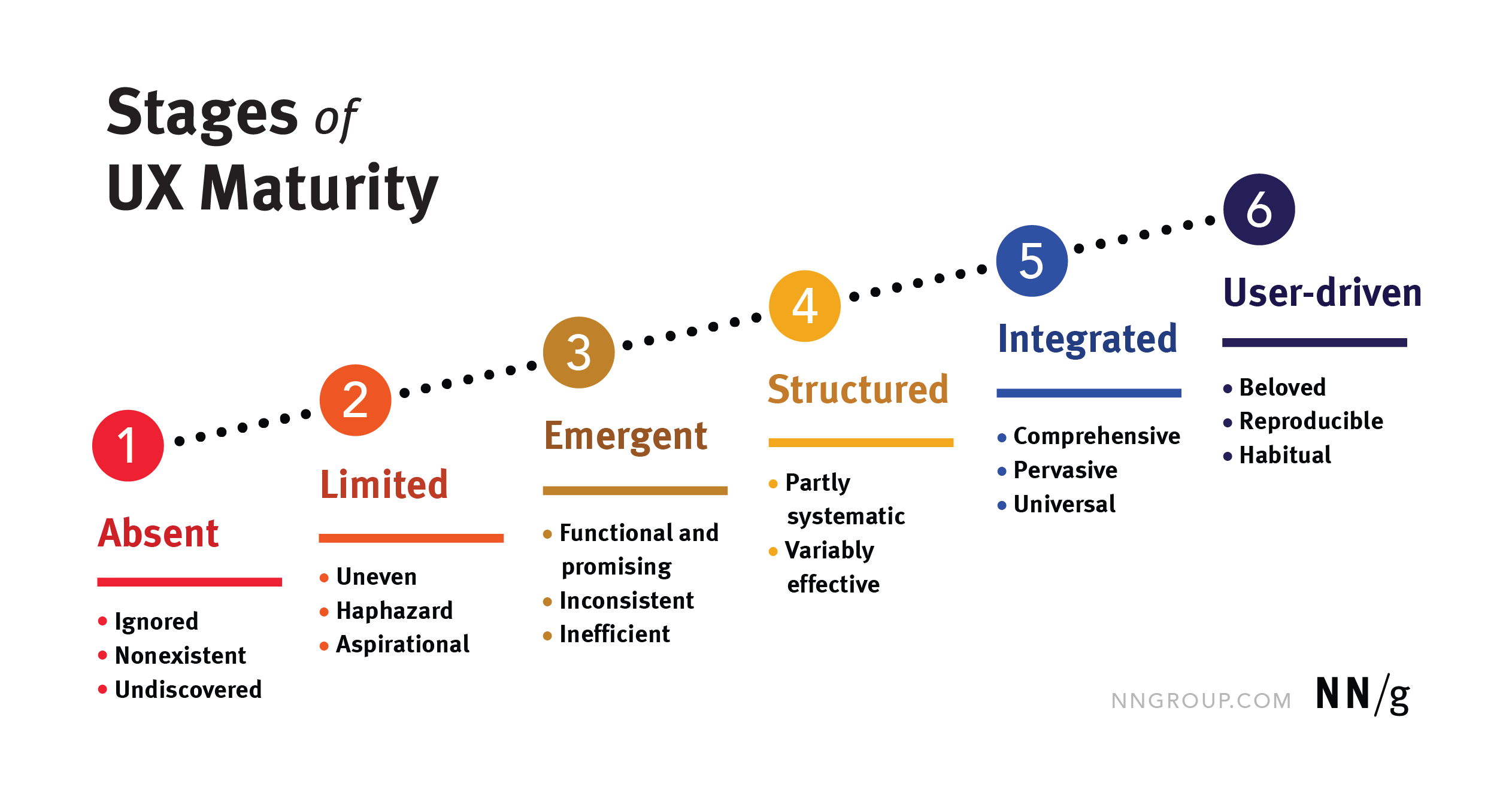

The 6 stages of UX maturity are:

- Absent ~ UX is ignored or nonexistent

- Limited ~ UX work is rare, done haphazardly, & lacking importance

- Emergent ~ The UX work is functional & promising but done inconsistently & inefficiently

- Structured ~ The organization has semisystematic UX-related methodology that is widespread, but with varying degrees of effectiveness & efficiency

- Integrated ~ UX work is comprehensive, effective, & pervasive

- User-driven ~ Dedication to UX at all levels leads to deep insights & exceptional user-centered–design outcomes

The UX-Maturity Model incorporates new norms & adapts to the evolution of our industry. It outlines how UX maturity can be shaped & measured. However, companies at the same stage might look different due to organization specifics such as size priorities, or politics.

Factors in UX Maturity

Improving UX maturity requires growth & evolution across several different factors, including:

- Strategy ~ UX leadership, planning, & resource prioritization

- Culture ~ Knowledge about & attitudes towards UX, as well as cultivating UX careers & practitioners’ growth

- Process ~ Systematic, efficient use of UX research & design methods

- Outcomes ~ Intentional definition of goals & measurement of the results produced by UX work

None of these factors stand alone; rather, they reinforce & enable each other. Knowledge of UX processes does not create a great UX team if UX work is not prioritized by the organization’s leadership; likewise, belief in the value of UX only becomes actionable when there are methodologies in place to ‘practice what you preach.’ Organizations must progress in all these dimensions in order to reach high levels of UX maturity & realize the full value of user-centered design.

Each of these 4 high-level factors influence the organization’s UX-maturity level. These factors provide a framework to assess the organization’s commitment to UX & its ability to deliver user-centered products & services across all areas of the organization.

Strategy

Strategy includes all high-level decisions & planning that contribute to the success of UX work before it begins. There is always a different method or strategy that could be used to get an effective, positive result. However, unlike a vision, strategic plans offer a systematic, sequential strategy for getting to the future. This includes specific, quantifiable objectives.

Having said that, strategy can be broken down into 3 subfactors:

- Vision ~ One or more declared user-centered organizational objectives that guide internal, crossdisciplinary decision making are key to UX maturity. This subfactor considers whether things like yearly objectives, crossdepartmental alignment, & leadership are UX-oriented.

- Logistics ~ In order for UX work to prosper, UX efforts should be accounted for & prioritized, throughout the product lifecycle. This subfactor accounts for whether aspects like development schedules & processes, operationalized systems, & standardized decision making take UX into account.

- Budget ~ Organizations must allocate adequate resources ~ people & time ~ to UX & invest in future UX initiatives.

In low-maturity organizations (stages 1–3), a vision that includes UX is rare (or if it even exists, isn’t well-communicated). In high-maturity organizations (stages 4–6), a vision includes strong, thorough user-centered ideas, is deliberately & strategically communicated, & guides the entire organization (UXers & everybody else).

Low-maturity organizations’ schedules & development processes seldom mention UX, & if they do, UX is used to validate or improve existing designs, rather than drive new ones. In contrast, high-maturity organizations implement a shared method for project prioritization, regularly track user-experience quality, & allow good research to drive projects.

Low-maturity organizations are marked by a lack of full- or part-time UX people & use only budget scraps to fund UX projects. The few UXers they have are spread too thinly across multiple product teams. High-maturity teams have adequate UX budgets that are allocated mindfully & systematically (rather than haphazardly & inconsistently). UX work is prioritized & resources are used both for refining existing designs & creating new product capabilities that respond to users’ needs.

Culture

Every company & organization has its own unique personality & culture. Until changes sink deeply into an organization’s culture ~ a process that can sometimes take years ~ new approaches are fragile & subject to regression. The opportunity to create organizational culture ~ a culture built around sound business ethics, helps assess the culture & associated strengths, weaknesses, & potential opportunities.

Culture encompasses ideas that contribute to the organization’s understanding of the purpose & value of UX. There are 4 subfactors that enable a positive UX culture:

- Awareness ~ This subfactor looks at how widespread knowledge of UX & its benefits is across the organization (beyond the UX staff). It includes an organizational-wide interest in learning UX.

- Empathy ~ For UX to succeed & thrive, people outside the UX team must support & be involved with UX work. Widespread respect for UX, proactive assistance, positive reinforcement, & championing by others are important.

- Competency ~ This subfactor captures how well-defined skills related to UX practice & expertise are & how much they are cultivated throughout the organization. This subfactor looks at whether the organization has dedicated UX-roles, a breadth of skills in UX teams, & pertinent hiring practices.

- Adaptability ~ For UX to evolve, a spirit of persistence, flexibility, & sustainability around UX work is key. This subfactor addresses whether the organization is 1) willing to advance best practices & adjust approaches to improve, & 2) logistically able to adapt to changing needs.

In low-maturity organizations, the UX mindset usually doesn’t exist or if it does, there is leader-to-leader discrepancy & many think UX is just polish at the end of product development. In high-maturity organizations, there is a broad understanding that UX impacts products & services from the inception phase & applies beyond interfaces. In fact, a UX skillset often plays an equal role (& might be a prerequisite) alongside other skillsets.

Low-maturity organizations have leaders who are indifferent to UX & struggle with a lack of respect for the future-oriented aspects of UX (for example, discovery research) & inconsistent buy-in for UX across leaders & colleagues. In contrast, high-maturity organizations have strong assistance for good UX across teams, UX is well-respected among peers, & there is UX expertise & support at the highest level (C-suite).

In low-maturity organizations, there are usually no dedicated UX roles or titles. If there are any, the people in those roles cannot effectively sustain their work because they are part of teams that are not UX-minded. These organizations also often miss specific skillsets needed to establish UX basics like benchmarking or qualitative research. As organizations evolve to be high-maturity, human-resources elements (like job profiles & career paths) not only exist but cover a wide range of UX skills. Hires are made to specific UX-roles depending on team needs & UXers are encouraged to grow their skillset through mentorship & additional training.

Low-maturity organizations are often rigid when it comes to adjusting processes in order to incorporate a UX mindset or respond to new UX challenges. They may adopt some UX-oriented workflows but apply them undiscerningly & be unwilling to change them when facing new UX challenges or problems. They may also not have the capabilities or the knowledge to change their processes due to understaffing or lack of specialized UX expertise. Their UX practice may depend on one or two people; if these people leave the company, the practice dies. In mid-to-high maturity organizations, there is both a willingness & logistical ability to adjust processes based on the context & needs of the team. If personnel changes, the product team can continue without having to start from scratch.

Awareness, empathy, competency, & adaptability together create a positive, proactive culture where UX work can be understood, valued, & improved.

Process

In the process of serving others, we become an organization that people look to for help & guidance. A process that enables an individual to learn & seek guidance from a more experienced mentor who can pass on relevant knowledge & experience.

The process factor encompasses all UX work that occurs (research, design, content creation, etc.) within an organization. It breaks down into three subfactors:

- Methods ~ This subfactor addresses whether there is established use of user-centric techniques throughout the entire product lifecycle: design practices, qualitative- & quantitative-research approaches, & iteration.

- Collaboration ~ To be successful, UX teams must work with other departments. This increases common ground & the creation of diverse ideas.

- Consistency ~ This subfactor addresses the existence & utilization of shared systems, frameworks, & tools that allow consistent inclusion of a UX mindset in various processes & free practitioners to think strategically.

Low-maturity organizations suffer from a lack of methods, often used incorrectly. Also, in such organizations, UX methods are frequently used in response to a specific business need, rather than being embedded into everyday work. Research is limited to ‘easy’ methods instead of appropriate methods; findings from research rarely lead to design changes. In comparison, in high-maturity organizations, a variety of design & research methods are used across the entire development lifecycle. Iterative design is common & discovery research is a prerequisite for most projects. Extremely high-maturity organizations may even create new methods or refine existing ones & set new industry standards.

Low-maturity organizations don’t realize that crossfunctional teams should be involved in UX; rather, they think that only those with “UX” in their title should be responsible for UX. In these cases, inconsistent success metrics make collaboration difficult & cause it to occur only for part of the development process. In high-maturity organizations, collaboration is embedded in the company’s DNA. UX professionals routinely cooperate with other roles & most teams perform regular standups & retrospectives.

The only common thread related to UX in low-maturity organizations is that any UX activities are one-off &, thus, not reproducible or comparable. High-maturity organizations invest in establishing consistent tools, training, information, & resources around UX design & research. Frameworks exist across the organization & are shared, maintained, & improved. This approach ultimately ensures that the design process can be similarly applied across teams & projects in a sustainable manner.

Outcomes

This factor highlights the result of UX research & design. These outcomes of UX work should be intentionally defined by establishing clear UX goals & objectives that are explicitly documented, shared, & measured by the product team & its stakeholders. This is a key factor in UX maturity because it allows organizations to understand the effectiveness of UX work overtime. Outcomes comprise two subfactors:

- Impact of the Design ~ Success, at a company level, should be rooted in meeting not just business goals, but also the needs of real users. This subfactor looks at the quality & effectiveness of the implemented design from a user-centered perspective.

- Measurement ~ This subfactor addresses the mechanisms in place to track the impact stated above. An organization should have clear user-centered metrics & a process in place for tracking them.

In low-maturity organization, the success of the design is based on a checklist of feature capabilities, rather than usability & user needs. In high-maturity organizations, the success of the design is based on how much it answers the project goals & meets real user needs.

Low-maturity organizations usually chase metrics that have nothing to do with the user. Even if they do have a few token user-centered metrics, there is no system in place to track them. High-maturity organizations have user-centered goals that drive metric creation. These metrics are effective at measuring UX, encompass aspects of the entire user journey, are monitored & updated, & are used at the highest leadership level.

However, in practice, things are a little more nuanced. In some organizations, certain factors may carry more weight than others. For example, in extremely traditional, hierarchical companies, Strategy may impact an organization more than process (due to leadership being more likely to play a role in dictating process standards that are respected & followed). Inversely, in startups, where there is little strategic planning & a quickly evolving vision, the Process factor (& its subfactors) may play a larger role in the overall maturity.

Given this contextual complexity, a complete evaluation of an organization’s UX maturity should be based on diverse, company-tailored assessment methods, including conducting research, observing work practices, interviewing & surveying employees at different levels in the organization, analysis of processes, people, tools, & deliverables.

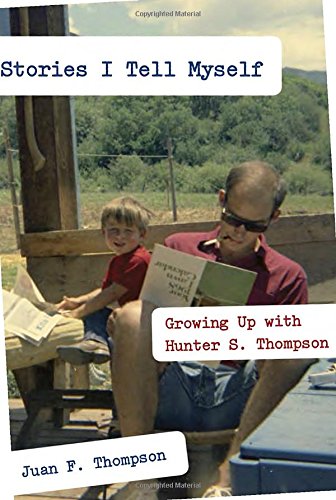

“Hunter was a deeply sentimental man, & like most sentimentalists, he was a pack rat, because such people, & I am one, confer on objects the essence of a person, place, or event. They are tangible reminders of the good & significant, & they are more than simply reminders, they are talismans, objects consecrated by memory. They have magical properties & they are not to be lightly disposed of or given away, because in losing them we lose a part of our memory, & memories are the bricks of the houses of our selves, our lives.” ~ Curated Excerpt From: Juan F. Thompson. “Stories I Tell Myself.” Apple Books.

Curated via Nielsen Norman Group. Thanks for reading, cheers! (with a glass of wine & book of course)

2017 Grand Napa Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon

Producer: Grand Napa Vineyards, Napa Valley, Napa County, North Coast, California, USA

"The 2017 Cabernet Sauvignon offers terrific crème de cassis, crushed violets, candle wax, & hints of sappy herbs as well as a beautifully textured, layered style on the palate. It's the star of the show from this team, has terrific purity of fruit, & should drink nicely for over a decade." ~ 92 Points ~ Jeb Dunnuck

"A red with aromas & flavors of blueberries, currants & lemon rind. Full body. Plenty of fruit with a spicy, hot-stone finish. 86% cabernet sauvignon & 14% merlot. Drink or hold." ~ 92 Points ~ James Suckling

Stories I Tell Myself : Growing up with Hunter S. Thompson

Hunter S. Thompson, “smart hillbilly,” boy of the South, born and bred in Louisville, Kentucky, son of an insurance salesman and a stay-at-home mom, public school-educated, jailed at seventeen on a bogus petty robbery charge, member of the U.S. Air Force (Airmen Second Class), copy boy for Time, writer for The National Observer, et cetera. From the outset he was the Wild Man of American journalism with a journalistic appetite that touched on subjects that drove his sense of justice and intrigue, from biker gangs and 1960s counterculture to presidential campaigns and psychedelic drugs. He lived larger than life and pulled it up around him in a mad effort to make it as electric, anger-ridden, and drug-fueled as possible.

Now Juan Thompson tells the story of his father and of their getting to know each other during their forty-one fraught years together. He writes of the many dark times, of how far they ricocheted away from each other, and of how they found their way back before it was too late.

He writes of growing up in an old farmhouse in a narrow mountain valley outside of Aspen ~ Woody Creek, Colorado, a ranching community with Hereford cattle and clover fields . . . of the presence of guns in the house, the boxes of ammo on the kitchen shelves behind the glass doors of the country cabinets, where others might have placed china and knickknacks . . . of climbing on the back of Hunter’s Bultaco Matador trail motorcycle as a young boy, and father and son roaring up the dirt road, trailing a cloud of dust . . . of being taken to bars in town as a small boy, Hunter holding court while Juan crawled around under the bar stools, picking up change and taking his found loot to Carl’s Pharmacy to buy Archie comic books . . . of going with his parents as a baby to a Ken Kesey/Hells Angels party with dozens of people wandering around the forest in various stages of undress, stoned on pot, tripping on LSD . . .

He writes of his growing fear of his father; of the arguments between his parents reaching frightening levels; and of his finally fighting back, trying to protect his mother as the state troopers are called in to separate father and son. And of the inevitable ~ of mother and son driving west in their Datsun to make a new home, a new life, away from Hunter; of Juan’s first taste of what “normal” could feel like . . .

We see Juan going to Concord Academy, a stranger in a strange land, coming from a school that was a log cabin in the middle of hay fields, Juan without manners or socialization . . . going on to college at Tufts; spending a crucial week with his father; Hunter asking for Juan’s opinion of his writing; and he writes of their dirt biking on a hilltop overlooking Woody Creek Valley, acting as if all the horrible things that had happened between them had never taken place, and of being there, together, side by side . . .

And finally, movingly, he writes of their long, slow pull toward reconciliation . . . of Juan’s marriage and the birth of his own son; of watching Hunter love his grandson and Juan’s coming to understand how Hunter loved him; of Hunter’s growing illness, and Juan’s becoming both son and father to his father.